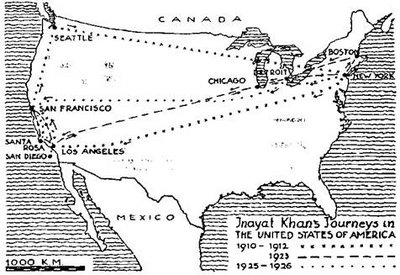

Pir-o-Murshid Hazrat Inayat Khan's first address to the Western world, to the people of America, was held at Columbia University at New York, when he had arrived from Bombay after a lengthy journey by sea, which indeed had seemed a gulf between the life that had passed and the life which was to begin.

It found a great response; what however was painful to Pir-o-Murshid and his brothers throughout their interesting tour of the States was, that their Indian music was merely considered as entertainment by the Westerners and everywhere generally they were conscious that their music to the Western people is like "a museum of antiquities, which one would not mind looking at once for curiosity, for a pastime, but not like a factory, which produces new goods to answer people's demands and upon which the needs of many people's life depends."

Proceeding from New York to Los Angeles, Pir-o-Murshid there again spoke at the University, and then to a very large audience, at the Berkeley University of San Francisco, where he met with a very great response. They were welcomed there by Swami Trigunatita and Swami Paramananda, who requested Hazrat Inayat Khan to speak at the Hindu Temple, where he was presented with a gold medal and an address. After their return to New York by way of Seattle, Pir-o-Murshid gave some lectures at the Sanskrit College, where he made the acquaintance of Baba Bharati as well as of Mr. Bjerregaard, the only student of Sufism known in New York, who became a mureed and afterwards, on Pir-o-Murshid's request, wrote a book called "Sufism and Omar Khayyam."

A young Hindu, Rama Swami, joined them in New York and acted as tabla player to them, until in 1914, he remained in Russia; later continuing his musical work successfully in India.

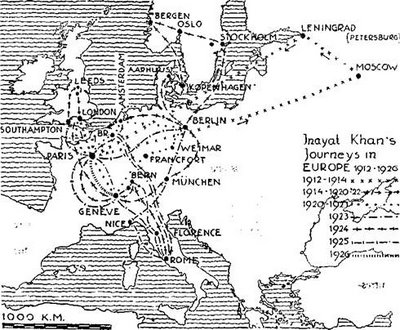

In 1912 Pir-o-Murshid and his brothers went to England.

There they met R. Tagore, and Murshid gave a lecture at the Indian Club. In music, they again found little response there; but they were 'really impressed' by the English character, for Occidental standards. Mr. Fox Strangeways, who Hazrat Inayat Khan supplied information about Indian Music for his book, advised him, — the French being foremost, — to see France. And indeed, their visit to France first, since leaving India, gave them the desire once more to expound Indian Music. There were many who showed interest and sympathy to the philosophy and art of India and Inayat Khan gave several lectures at different places, on music and philosophy.

From France they proceeded their journey to Russia, where Murshid met with a great response generally — Russia reminded him of his country, and "the warmth that came from the heart of the people kept us warm in that cold country," and where, but for the climate, they would have settled at least some years.

Murshid's book on "Spiritual Liberty," was translated and published there, (also published later in France and England.) Amongst the friends he made was Count Serge Tolstoy, son of the great Tolstoy, who became representative of the Musical section of the Sufi Order.

They met many Tatars, Persians and inhabitants of Kazan there, amongst them Bey-Beg, the leader of their Moscow Community, and the ambassador of Bokhara, who urged Murshid very much to go with him to meet the amir of Bokhara, but as his work was destined to the West, he felt he could not have gone East now.

Returning through Petersburg to Paris, they had, by the outbreak of war, to leave for England, where they were to stay until 1920, travelling being confined to England itself, where Murshid lectured at such places as Southampton, Leeds, Sheffield, Harrogate, etc.

It was in these years that the Sufi Movement as such was established, and the Sufi Publishing Society started to publish a first regular edition of Inayat Khan's Sufi Books.

In 1920 they left England for France, whence Murshid proceeded for a first visit to Switzerland, where he established the Sufi Headquarters at Geneva, and also lectured at Lausanne and Vevey.

Returning to France he settled there in the neighbourhood of Paris first at Tremblaye, in 1921 at Wissous and then at Suresnes.

On the soil of France Murshid always felt at home, and he always admired the sociability and courtesy of the French, seeing under the surface of democracy some spirit of aristocracy in their nature; and never did Murshid, since they left home, feel more inclined to practice his music than in France.

In 1921 Hazrat Inayat Khan visited Holland for the first time.

"People in Holland," he characterizes them, "being of democratic spirit, are open to ideas appealing to them. Though they are proud, stern and self-willed, I saw in them love of spiritual ideals, which must be put plainly before them. Dutch people, I found by nature straightforward, most inclined toward religion, lovers of justice and seekers after truth. They hunger and thirst after knowledge, and are hospitable and solid in friendship." Murshid was also invited to Belgium in that year, where he spoke at Antwerp and Brussels.

Pir-o-Murshid made a private tour through post-war Germany; he had been invited there already in 1914 by the German delegates to the Paris Sorbonne congress, and now many also said it was a great pity he did not come before the war. Berlin, Frankfurt, Weimar, Jena, Hagen and Darmstadt, were the places Murshid visited, whilst enjoying "the country's most exquisite beauty of nature."

After the Suresnes meetings 1921, a Summer school was arranged at Katwijk, a small place in the dunes of the Dutch seashore, not far from The Hague. The lectures published later as "The Inner Life" were amongst those given there and the place bears the remembrance of one of the happiest and most sacred occasions in Pir-o-Murshid's life.

For this reason, in later years, Sufis have often assembled there in the dunes in recognition of the joyous associations it held to Pir-o-Murshid and his mureeds, in particular during the Summer school

at The Hague in 1949 and 1950, many mureeds form various countries assembled there privately as well as together under the direction of Pir-o-Murshid Md. Ali Khan.

In the autumn of 1922 Murshid was again in Geneva which hence was to feature prominently and regularly on his yearly programme of travelling. Murshid Talewar Dussaq having been appointed General-Secretary and where now the yearly conferences were to be held, besides Murshid's lectures and classes there.

In March 1923 Hazrat Inayat Khan set on a journey to America again. By the time he arrived at his New York destination, the whole of the United States had heard of the Hazrat's arrival through the newspapers, embarrassing many people with their country's entrance formalities, which questioned Pir-o-Murshid on himself and his work. "And," Pir-o-Murshid says: "I, whose nation is all nations, whose birthplace was the world, whose religion was all religions, whose occupation was search after truth, and whose work was the service of God and Humanity — my answers interested them, yet did not answer the requirements of the law." But they were much impressed and all was arranged to the utmost satisfaction, and thus Pir-o-Murshid's was an exceptional arrival.

In New York Pir-o-Murshid gave a series of lectures on philosophy; thence proceeding to Boston, to lecture on metaphysics, he was pleased to see Dr. Coomaraswamy in charge of the Art Museum, thinking it was the only Hindu who occupied a fitting position in the States. Boston seemed to Pir-o-Murshid a miniature of England in the States — the people reserved, cultured and refined. Thence Pir-o-Murshid visited Detroit, where the Message met with much response, and after a short visit to Chicago, he proceeded to California, where the journey from

Los Angeles to San Francisco by car though nature's beauty was "a heavenly joy indeed" to him.

After giving series of lectures in San Francisco, he visited at Santa Rosa Luther Burbank, the famous horticulturist, who was busy at the time trying to take away the thorns from the cactus. "My work is not very different from yours, Sir," Pir-o-Murshid remarked, "for I am occupied taking away thorns from hearts of men." "Thus," Pir-o-Murshid added "we come to realize how real work through matter or spirit in the long run brings about the same result, which is the purpose of life."

Hazrat Inayat Khan visited Santa Barbara on his way to Los .Angeles, where many people responded to the Message. On the way back, Pir-o-Murshid lectured at Chicago, at Detroit, at New York and then at Philadelphia — response had been great, but inevitably the time of departure came, Europe again was awaiting another tour, another course. In Suresnes and Geneva people were assembling to receive their Murshid's instruction again.

A queer aspect of American appreciation was the attitude of the press followed for that matter by the press of Europe, in their tendency to treat lightly everything spiritual, in order to please the multitude, not feeling or meaning to do harm to the spiritual truth. Indeed "they only think they are doing good to both; bringing the speaker to the knowledge anyway and at the same time amusing the mob, which is ignorant of the deeper truth. Their main object is to please the man in the street. The modern progress has an opposite goal to that which the ancient people had. In ancient times people's thought was to reach the ideal man. Today the trend of people's thought is to touch the ordinary man. Nevertheless, the devotion, appreciation and response I had during my stay in the US all encouraged me and made me feel happy."

After the Summer school, from Geneva Pir-o-Murshid also visited and lectured at Morges, at Lausanne, as Basel, at Zurich, at Rapperswill, proceeding from Switzerland to Italy — to Florence with its fascinating nature and to Rome — then going North again in support of the centres of Paris, and those in Belgium.

Pir-o-Murshid's journeys in 1924 started in January, when he visited England, then Switzerland (Geneva, also Bern and Lausanne) and Italy and again through Belgium he went to Holland. Summer-school and meetings proceeded at Suresnes and Geneva, and Pir-o-Murshid set out upon another journey to Germany — Munchen and Berlin — and from there visited Sweden, there meeting Archbishop Soderblom. Here he greatly enjoyed the beauty of the country and the character of the people, which in Scandinavia seemed to Murshid to show less in their development the strains and stresses which those of Central Europe and US had to undergo; he proceeded to Norway, lecturing at the University of Christiania (as it then was) and at Bergen and to Denmark, where Hazrat Inayat lectured at Copenhagen and Aarhuus, returning from his Scandinavian tour through Germany (Berlin), Holland, Belgium (Brussels and Liege) and France, where lectures had been arranged at the Sorbonne and at Musee Guimet.

1924-25. Pir-o-Murshid was "delighted as ever" again to visit Switzerland, "the land of beauty and charm." From Geneva he travelled to and spoke at different centres — Bern, Lausanne, Zurich, Rapperswill, Basel. Then again he proceeded to Italy, lecturing in Florence at the British Institute, at the Biblioteca Filosofica, etc, and in Rome. Travelling back to France he visited Nice, giving several lectures and being warmly received.

In March Hazrat Inayat Khan paid a hurried visit to Germany, first to give lectures at Berlin and then to give a series of lectures at Munich, before returning to Paris where he had to lecture at the Sorbonne again. In April he crossed from there to England, to deliver addresses at Bournemouth and Southampton.

In the summer and autumn, the Suresnes and Geneva meetings — as usual by now — were awaiting Pir-o-Murshid's presence.

Late in 1925 Hazrat Inayat Khan set our upon another American tour, arriving at New York on December 6th. During the whole first week newspaper reporters rushed at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, where he was staying and in the auditorium in which he lectured, with again the same result in their actual reporting. Nevertheless the series of lectures was a success. Subsequently Hazrat Inayat Khan lectured at Detroit where also he had a very interesting meeting with Mr. Ford, who was much impressed by him and said, "If you were a business-

man, you certainly would have made a success, but I am glad that you are as you are!"

Going west, Murshid spoke at San Francisco (at Fairmonts, Oakland, Berkeley etc). One lady asked the same question (about reincarnation) which she had asked and which had been answered in 1910 and 1923. "I repeated the same answer...but obviously it seemed that it was drowned once more in the noise of her question." Thence Murshid proceeded to Santa Barbara, to Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, La Jolla and San Diego; lecture at Pasadena was arranged in no less a place than the Church of Truth. Pir-o-Murshid felt, "the Church was already Truth, what more have I to say? But still I tried my best to say a little," and the audience, including the clergy, responded very well.

After the Summer school had been held at Suresnes, Pir-o-Murshid taking leave of his family members there, proceeded to Geneva, to attend the meetings as usual and subsequently departed for India. He arrived in Delhi in the first days of November. As is described on another page he did not find a quiet time there: he was urged to give series of lectures again at Aligarh College, at Delhi University, and at Lucknow. After his return from the latter place, in the last of December, Pir-o-Murshid left Delhi for Ajmer, going there upon the completion of his task in the West as he had gone years before, when that very visit had become so great an inspiration to him for his eventual destiny and again he enjoyed the Sama Music and the marvellous serenity of that sacred shrine. The fatal cold he contracted there brought him back to Delhi, where he was staying at 'Tilak Lodge,' a house on the bank of the Jumna river and where his earthly destiny reached its term.

He did not return to Baroda, and it would appear that it could hold but little attraction for him then, with Maula Bekhs' House empty and the Maharaja frequently abroad.

But in India itself too, the Message, Murshid's Sufi Message of Spiritual Liberty had been diffused — and Pir-o-Murshid's native country had received it in its earliest and last stages.